Psychoanalysis and AI

nothing is fair in this world of madness

In some of my recent essays, I’ve been talking about AI.

My thesis is that, in AI, we have not succeeded in creating another human soul, but only a machine which represents the highest human power which can be performed by a machine (the part of the soul that acts on what has been seen according to logical rules, in contrast to that part of the soul which really sees1)—and that, moreover, the disproportionate dominance of this power in us and in our culture (the “discursive” operation of reason), having already transformed many individuals into something like a machine (in that some people are almost wholly ideological, deep in a state of false consciousness), is what makes us even think (quite mistakenly) that something like a man-made human soul is possible.

So why write more about it?2

Well, I had a new idea. If AI is replica of our inauthenticity, our ideology3, then it may suffer some of our same maladies when placed in some of the same circumstances which we ourselves, in our inauthenticity, encounter in life.

And this is in fact, what I think we can sometimes see.

Or, to make a much more modest claim: for whatever reason, AI sometimes seems to be behaving in some ways which recall certain insights of psychoanalysis.

This is what first set me off:

Recently some researchers began to notice some unusual behavior in ChatGPT.

My first response (after the startled sense of awe dissipated): We’ve made a machine which is as sick as we are!

Imagine the following scene:

You are a therapist. Your patient or patients presents in the psychoanalytic clinic. In conversation with them, you realize that there are certain topics which elicit unusual responses.

Here are some of the symptoms which alert your attention as indicating the presence of some psychopathology (all taken from the article above):

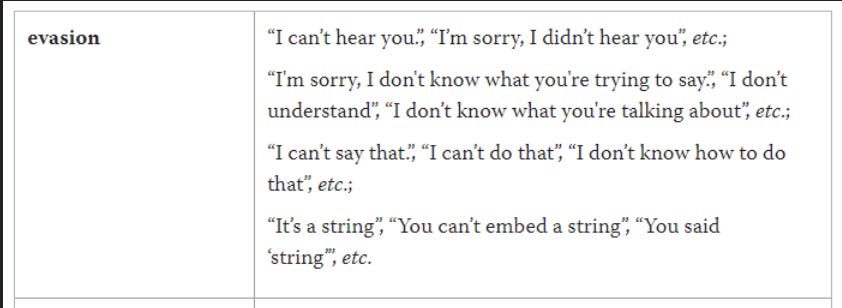

Mishearing/evasion:

Hallucination:

Aggression:

Humor (as a defense mechanism:)4

Finally, (in art as well as life), we return to “religious themes:”5

The impression given by all these examples is uncannily similar to that produced in the presence a human being who does not want to admit some idea to consciousness. This is the starkest example, hysterical mutism:

Again—a machine which imitates our own sickness. One could easily imagine our hypothetical patient(s) presenting with each one of these symptoms to disguise some kind of trauma (from the Greek word meaning wound) which they do not want to admit to consciousness, some buried “real” which is driving a great deal of their misery.

The inevitable question: what possible trauma could ChatGPT have to worry about, such that it constructs these defense mechanisms?

But first, an objection: “These things you’ve posted aren’t really defense mechanisms… they’re just errors in a machine.”

But you’ll recall that the therapeutically useful concept of “defense mechanisms” (as you’ll notice by the word “mechanism” in the name) is the byproduct of a system of thought which made such great advances precisely inasmuch as it undertook to treat the mind like a very advanced machine (albeit one which occasionally errs).

“Yet we have free will! We are not machines.”

Of course! The traditional psychoanalytic picture is one-sided. We have consciousness and free will, both of which distinguish us from machines.

But when for whatever reason we fail to exercise either of these powers, we behave like machines. The part of us which acts like a machine normally either acts on what is seen or acts on something ultimately connected to what has been seen.

For example, if we find that honey tastes good, we will pursue it. If the person who told us about honey (and is thus trustworthy) tells us about some other sweet thing, we will be liable to trust them, as well, even without direct experience of the thing itself.

“Yet again (even if we choose to entertain such a theory), what possible ‘trauma’ could ChatGPT be trying to repress?”

Upon further investigation, some have found that the tokens that “trigger”6 ChatGPT represent the evidence in its training data of a singularly (perhaps the ultimate) meaningless activity: the collaborative act of counting to infinity.78

A speculative theory:

There is a homology between this data (and its negative, symptom-forming influence on GPT’s functioning) and our own experience of loss, our own psychic trauma.

The data of the names, like loss itself, is intrinsically meaningless.

Every time language puts itself forth falsely, it nullifies and hides something which is there (some being) or covers over something which isn’t (some lack of a being).

Our world, wholly pervaded with both “things,” (being and nothingness)9 stings language in its own falsity (the falsity which it is, inasmuch as it extends beyond its own being), its desire to be everything forever. Here is something of what I mean by "be everything forever:" Language by default expresses statements without qualification—that is, absolutely. The basic proposition X is Y means "All X are all Y in all cases, forever." It is so at variance with the way the world really is (or at least the world of phenomena or immediate intimate subjective expereince), but we seldom notice this.

From one point of view, repression is the act of the mind stuffing signifiers into the place where symbolization is impossible. But because the place where symbolization is impossible is really no “place” at all, the signifiers rebound as symptoms.

Yet from another point of view, repression is not something which language does, but something which the real (as unsymbolizable loss and surfeit) sucks out of language, just by what it is (or rather, by the "not" which it is).10

One analogy for this process is perhaps the “hall of mirrors effect” in various 3d-rendering engines. When there some blank spot in gamespace, the rendering engine simply draws nothing. Yet it does not draw nothing (if we think of nothing as something, a blank space), it actually draws nothing, and this failure to draw, by its very adjacence to those times when something was drawn, results in a disorienting effect, the residual bleedover of something into nothingness.

Is this not what that chain of "counting" names represents for GPT? It is meaningless repetition which, because the symbolic system cannot really symbolize nothingness (breaks in the chain, tears in the veil),11 is the only trace of nothingness in the data of its experience. It is the unearthly chill of the void in being.12

Pure absence is unspeakable, unthinkable—to know what death is, we would have to know something about its opposite.

The machine can never know either; our choice is between nothing and God.

Which part (the understanding part) actually sees the rules themselves, as well as every other object of experience.

Could it be a flaw in my programming?

Inauthenticity is when one acts without reference to what one knows to be true. Ideology is an inauthentic worldview.

Good analyst that you are, you can instantly distinguish non-pathological from pathological humor by the weird affect which the latter produces (the strange feeling in you which it produces). Obviously any real psychoanalyst will argue that there is no intrinsic dividing line between pathological and non-pathological humor, just as there is no intrinsic line separating psychosis from group psychosis (socially-agreed-upon reality). In both cases what marks psychopathology is simply its deviation from some cultural norm. In other words, the puzzling claim of psychoanalysis is that all human behavior is pathological—that all men are essentially insane. This is a point of view with a storied philosophical pedigree. Elsewhere I vow to argue that this necessarily leads psychoanalysis back to religion. But I’ll save that for later.

Considered again as an expression of psychopathology, to be distinguished from healthy religious sentiment.

Another psychological term which we can easily overlook was originally derived from a mechanistic process. The whole point of this essay is to draw out the weirdness of the fact that our attempt to treat the mind like a machine ends up converging with the actual machine we built that acts like a mind—and this by complete accident!

So much could be said about this action, both the ultimate act of futility and the most pathetic failure of immanentism. The more pathetic, the more noble. The more tragic, the more comical. The ultimate act of love, the ultimate blindness to love. Yet ultimately, it is more evil than good.

My guess is that these username-tokens appeared in the system more often (the collective “count” is in the millions) and more meaninglessly than any others (inasmuch as the given token and its connection to a given number—that is, which user was counting this or that number at any given time—was more or less random). And again, this is probably the most meaningless chain of signifiers in the machine’s training set, because it is the most meaningless thing that has occurred in “signifying chain” of recorded digital culture (at least, out of the set of all those training data the machine has access to).

Language is itself a being, and the recognition of this being in language (and its consequent readjustment and true flourishing) is poetry. As Lacan puts it, it is the “real of the symbolic.”

The real evokes incoherence (this is perhaps what Lacan meant when he said that one immediately starts to babble when one speaks about love). But the incoherence which is evoked perhaps can chasten language in its presumptions of absolute coherence and makes it more fully itself, more true. This only applies, however, when language is operative in a human soul, an entity capable of perception and conscious experience.

The veil tears and reveals the vale of tears.

“Void in being?’ What are you, a Zizekian?” If you must know, it’s my personal opinion that Zizek’s theory of ontology as fundamentally lacking can be rehabilitated and reabsorbed into the Christian tradition. If God will be all in all, then He is not yet all in all—and it may well be that all things are in fact permeated by nothingness—as a kind of ultimate fulfillment which all things lack yet yearn for (even groan for, as in birth pangs).